Gigaton Potential

By protecting currently degraded land and allowing natural regrowth to occur, committed land could sequester 1.4 tons of carbon dioxide per acre annually, for a total of 54.5–85.1 gigatons of carbon dioxide by 2050. Protecting existing forests is also key; Forests account for 92% of all terrestrial biomass globally, storing approximately 400 gigatons of carbon dioxide (or 12.5x the total emissions emitted by oil and gas in 2021).

For reference: in 2019, the world emitted 51 gigatons of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gases. Project Drawdown estimates we need to cumulatively eliminate 1,000 GT from 2020-2050 to keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius.

You Might Be Interested If...

You are interested in emerging markets and international development

You appreciate the great outdoors and want to preserve forests for generations to come

You care about protecting biodiversity (tropical forests are home to 30 million species of plants and animals!)

What You Should Know

It is estimated that 287 million hectares of degraded land in the tropics could be restored to continuous, intact forest. Using current and estimated commitments from the Bonn Challenge and New York Declaration on Forests, the Project Drawdown model assumes that restoration could occur on 161–231 million hectares. The specific mechanics of restoration vary. The simplest scenarios include protecting the existing forests today or restoring land back into forests. Protective measures can keep pressures such as fire or grazing at bay. Other techniques are intensive, such as planting native seedlings to accelerate natural ecological processes. Local communities need to have a stake in what is growing if restoration is to sustain.

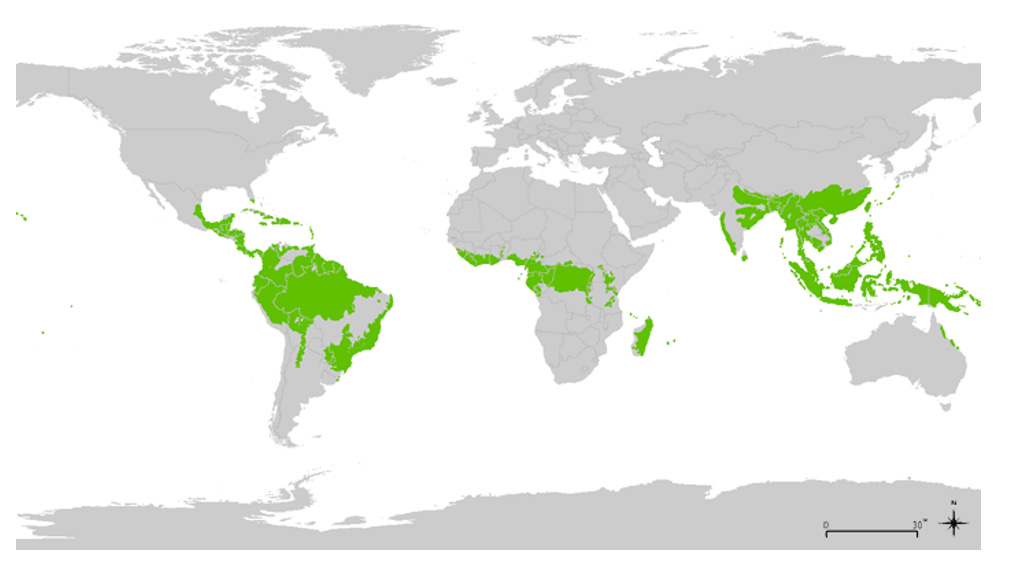

These tropical rainforests are located between the latitudes of 23.5°N (the Tropic of Cancer) and 23.5°S (the Tropic of Capricorn) in countries like Central and South America, western and central Africa, western India, Southeast Asia, the island of New Guinea, and Australia.

Map of the Tropical Rainforests

There are many pathways to impact this space. The Nature Conservancy has done significant research identifying ways to protect these natural ecosystems. Examples include avoided forest conversion, climate smart forestry, sustainable forest plantation management, forest fire management, avoided wood fuel harvesting, and reforestation. Indirectly, a large portion (42%) of the Nature Conservancy’s maximum reforestation mitigation potential depends on the reduced need for pasture accomplished via increased efficiency of beef production and/or dietary shifts to reduce beef consumption. Watch out for a future Gigaton article on the importance of plant-based diets.

Key Players

Avoided forest conversion businesses focus on making forests more lucrative to protect than destroy. The main business models include carbon credits, products, and ESG compliance. For example, NCX has protected over 4 million acres of forest by selling carbon credit to corporations with net-zero goals. Forested Foods works with the locals to harvest local honey from trees instead of cutting down the trees for lumber.

For forest plantation management, there are new plantation companies reimagining the entire timber logging process to create positive externalities on the environment. Komaza focuses on revitalizing deserted lands into thriving micro forests, planting 7M trees to date with 22,000 smallholder farmers. This gives local consumers access to sustainable timber and fuel at competitive prices, reducing pressure on Kenya’s remaining forests.

Climate-smart forestry is characterized by large timber companies that have shifted their practices to focus on environmental sustainability. Weyerhaeuser, a large American timber company, has its entire portfolio audited by the Sustainable Forest Management Standard to verify its responsible forestry management through third-party audits.

For forest fire management, there is a wave of startups leveraging remote sensing, AI, and analytics to predict wildfire risk. These companies sell insights to a range of customers from firefighter stations to insurance companies to electric utilities.

Reforestation companies are driving efficiencies throughout the reforestation process and identifying new business models to plant trees. Some are leveraging drone technology and AI to shoot seeds and plantings from above, dramatically reducing the time and cost to reforest a region. Others are using synthetic biology to grow trees faster and make them less vulnerable to carbon leakage such as Living Carbon.

Startups are innovating on cleaner cookstoves to reduce the need to cut down trees for fuel in the developing world. While almost 100 million people gained access to clean cooking between 2015 and 2018, achieving universal access by 2030 will require a major acceleration in the pace of change.

Opportunities for Innovation

🌿 Financing for nature-based climate solutions is minuscule

Even though land-based climate solutions appear in more than 75 percent of individual country commitments to the Paris Agreement, renewable energy, energy efficiency, and clean transport together receive nearly 30 times the amount of public mitigation investment that land-based solutions receive. We need more innovative financing mechanisms (blended finance, blue bonds, reverse-catastrophe bonds, and more), policy incentives to protect nature, and innovative startups to make a dent here.

🌿 Impact can be difficult to measure and incentivize

Challenges in measuring or predicting the effectiveness of NCS, especially the co-benefits like improved biodiversity, can lead to high uncertainty about their cost-effectiveness compared to alternatives. Current payments for ecosystem services are fragmented and not user-friendly.

🌿 Subsidies

Subsidies incentivize detrimental impacts on natural ecosystems. Business for Nature estimates that the world is spending at least $1.8 trillion a year, equivalent to 2% of global GDP, on subsidies that are driving the destruction of ecosystems and species extinction. We need subsidies and incentives for preserving nature to scale.

Sources

https://drawdown.org/solutions/tropical-forest-restoration/technical-summary

https://www.conservation.org/blog/3-ways-climate-change-affects-tropical-rainforests

https://www.paulsoninstitute.org/conservation/financing-nature-report/

https://cleancooking.org/reports-and-tools/2021-industry-snapshot-report/

https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-co2-emissions-in-2021-2

Stella, thanks for this informative post. I had a few questions:

1. With increasing evidence that stressed forests in different parts of the world (e.g., the rapidly depleting forests here in British Columbia and the Amazon) are losing their ability to capture carbon and becoming net carbon emitters, what does that mean for the future? So many “commitments” rely on the simple logic of trees + air = less carbon; what happens in a world where that is no longer true?

2. The argument that these lands can be returned to productive forests seems to be a vast oversimplification of the situation—how do the intersecting needs and wants of Indigenous rights holders, capitalist industry, and small- or large-scale landowners come into the picture here? What is an achievable approach to produce significantly larger tracts of protected forest in a world where land is a commodity that people fight for and steal? (Sharply illustrated by the aggressive increases in Amazon deforestation on Indigenous land in the Bolsonaro era—land deliberately set aside for protection is being slashed and burned for pasture by angry cowboys.)